A Hidden History of Russian Tattooing

In collaboration with Herman Deviashin

Before Rebellion, There Was Ritual

Before Russian tattoos became symbols of rebellion and criminal status, they were tools of identity, healing, and protection. The earliest roots of this history trace back to Indigenous and nomadic groups across Russia’s vast and fractured landscape, peoples whose cultures were nearly erased under Soviet rule, but whose traditions left a permanent mark on skin.

Indigenous Tattooing Traditions

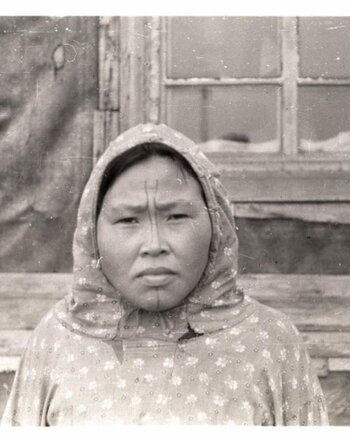

Across regions like Yakutia and Chukotka, women led the practice of tattooing. Patterns were sewn into the skin using reindeer hair and soot, creating dotted lines along the hands and face. For the Ainu of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, tattoos were carved into flesh with a small knife called a makkiri, then filled with pigment. These marks weren’t just decoration; they signaled status, offered protection from harm, and helped identify individuals within their community.

Each culture had its own system. The Pazyryk, whose tattooed mummies were found in the Altai Mountains, used tattoos to indicate rank. In Dagestan, tattoos were often private, coded markings that identified a person's clan or community. In every case, tattoos served as living records of identity, belief, and belonging. And in nearly every case, the practice was eliminated under Soviet assimilation. Most of these cultures transmitted their knowledge orally. Once disrupted, little was left behind; however, in some areas, the ritual continued, though in a modified form.

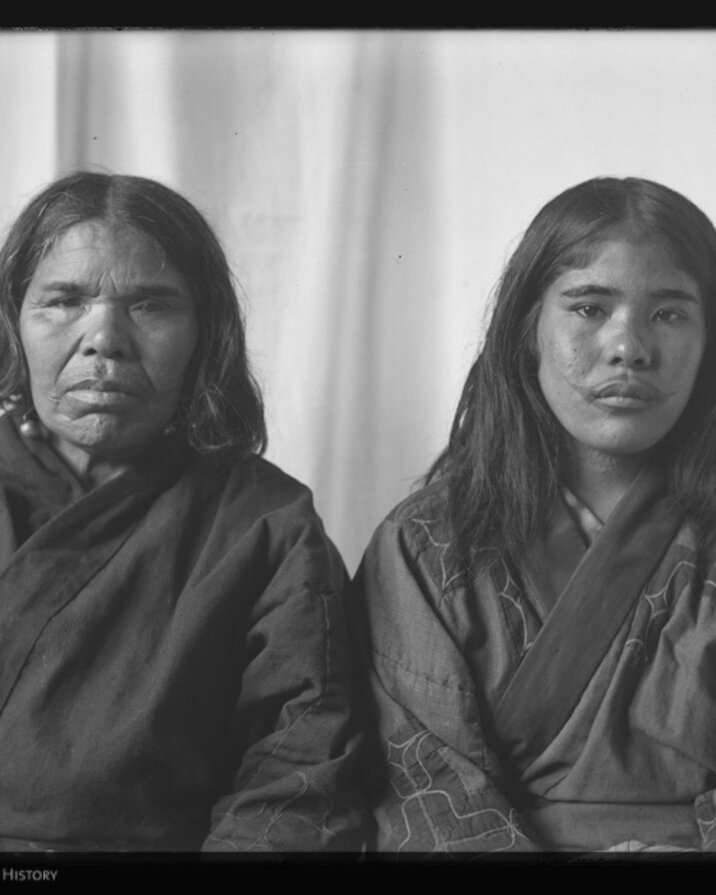

Chukchi women from Uelen with face tattoos, Chukotsky district, 1958.

Photo By: Sergey Arutyunov

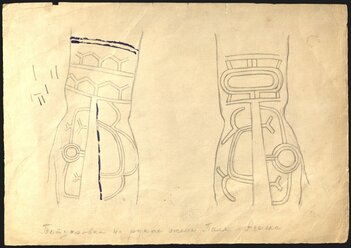

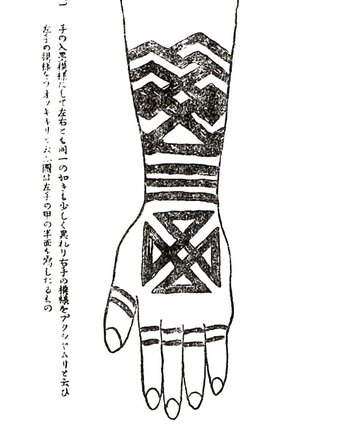

A drawing of hand tattoos, created in the early 20th century.

Ainu women

Indigenous Tattoo Drawings

Makkiri Knife used by the Ainu

Tattooed skin of mummies from the Pazyryk, State Hermitage Museum.

Photo Credit: Archaeology Magazine

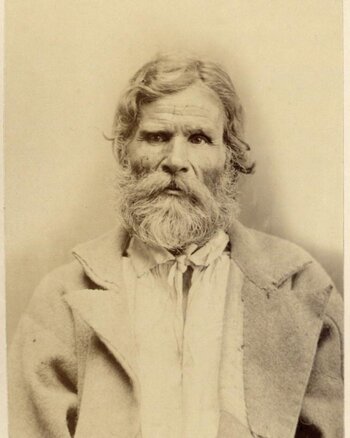

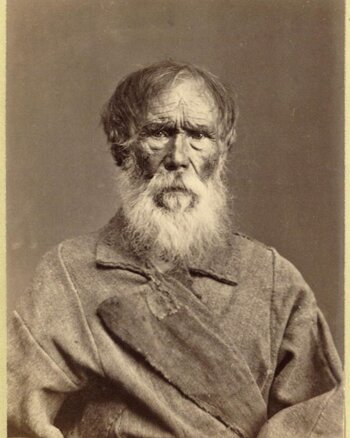

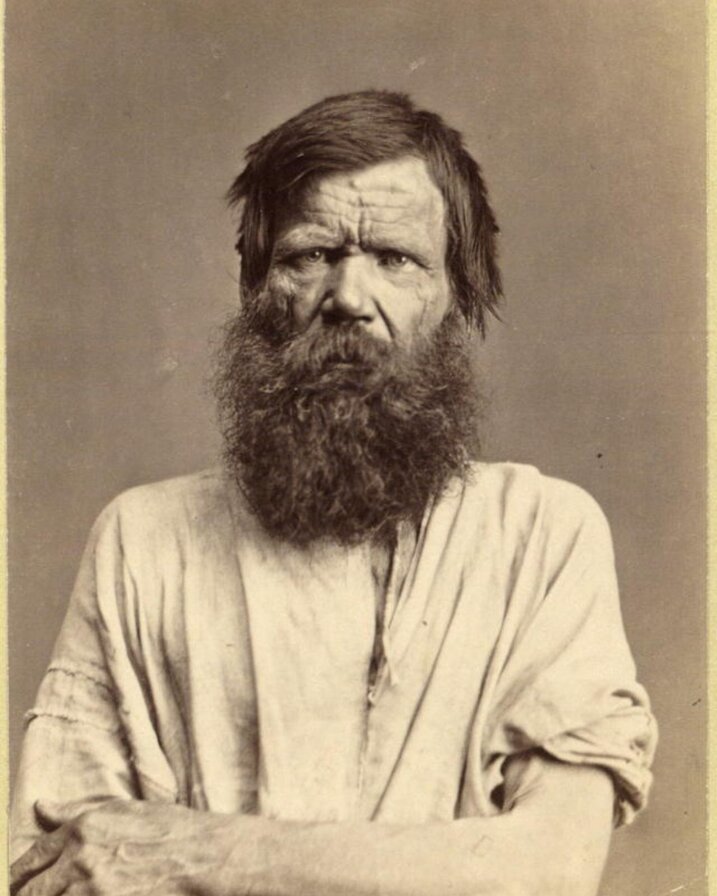

From Ceremonial to Punitive

When the Soviet state emerged, it introduced a new form of skin marking: not ceremonial, but punitive. Criminal branding in Russia dates back to the 1600s. Letters like KAT (hard labor) and RAB (slave) were burned or tattooed onto foreheads and cheeks. These were not just metaphors; they were deliberate acts of erasure, stripping away dignity for all to see.

TAT Branding tool

BOP Branding tool

Spring-loaded Branding tool

Underground Resistance in the Gulag

Yet this form of marking, intended to stigmatize, was gradually reclaimed. Inside labor camps, tattooing became an underground practice, serving both as communication and a means of survival. As the Gulag system expanded in the 1920s and 1930s, a secret visual language started to develop. It was never documented in writing. Instead, it was created body by body, mark by mark, often by people whose only crime was refusing to conform.

Gulag or Glavnoye Upravleniye LAGerey concentration and correctional labor camps, the Soviet Union, 1919.

Photo Credit: Gulag Online

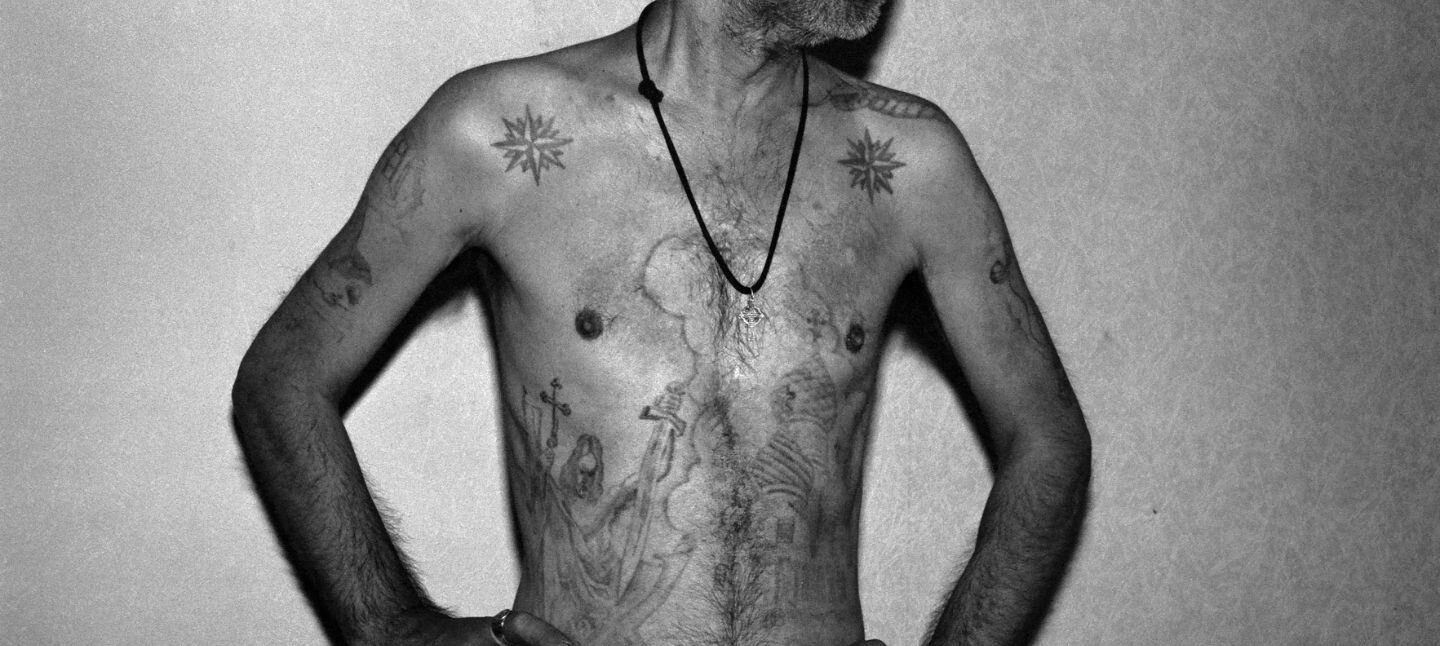

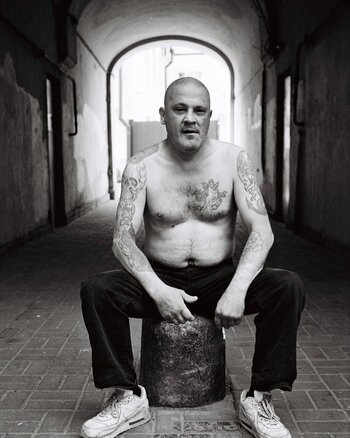

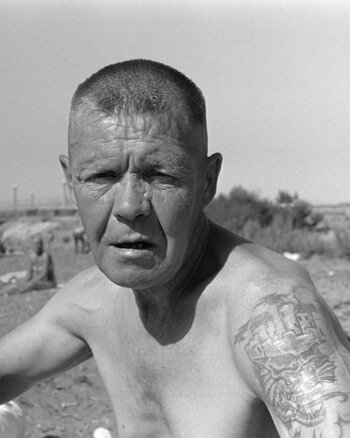

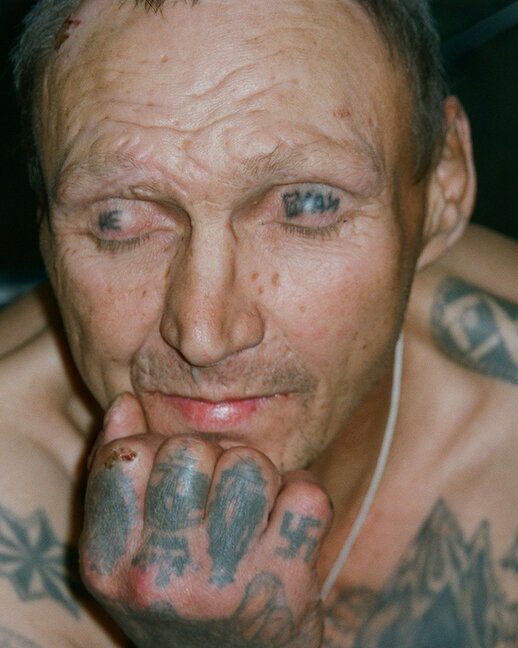

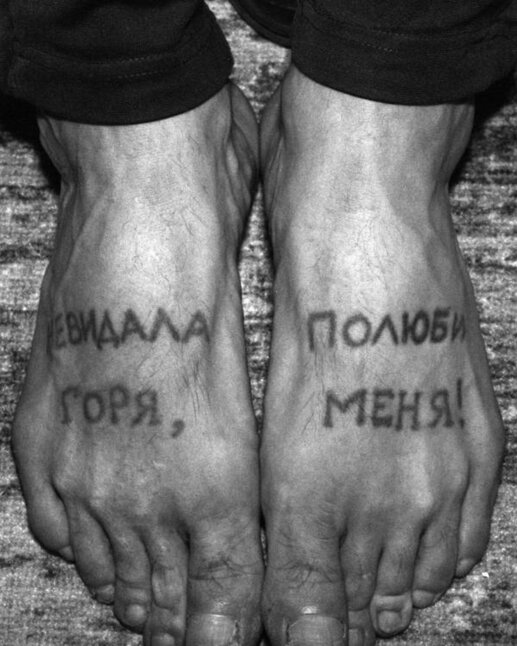

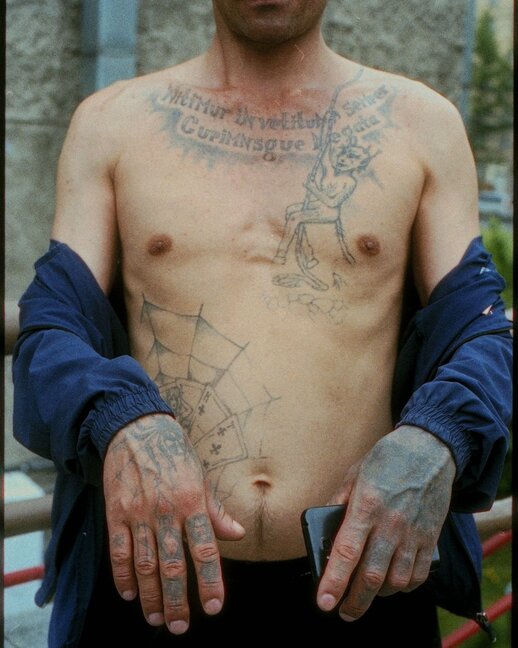

The Codes and Craft of Survival

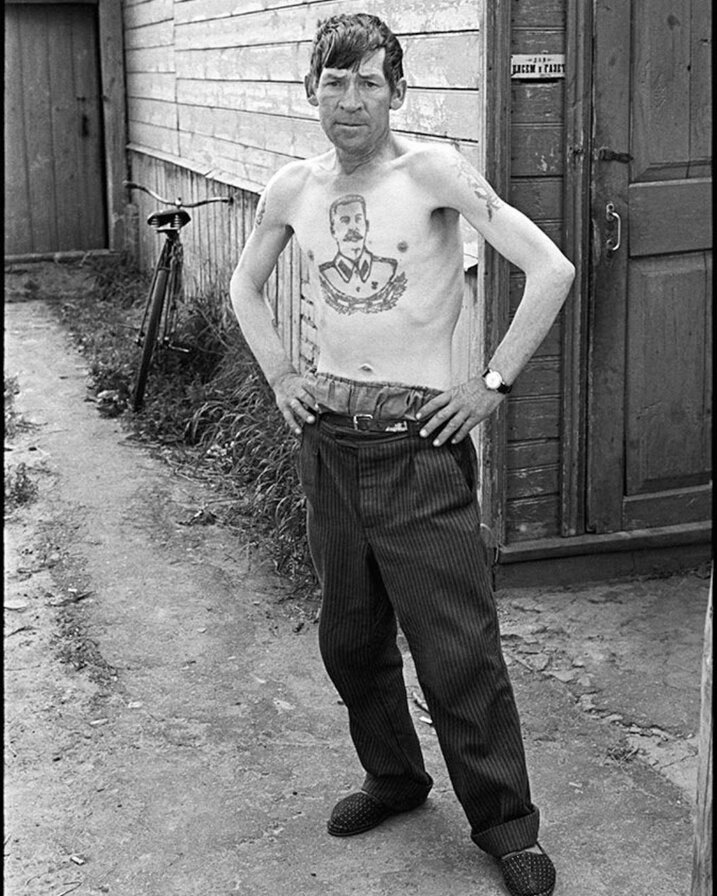

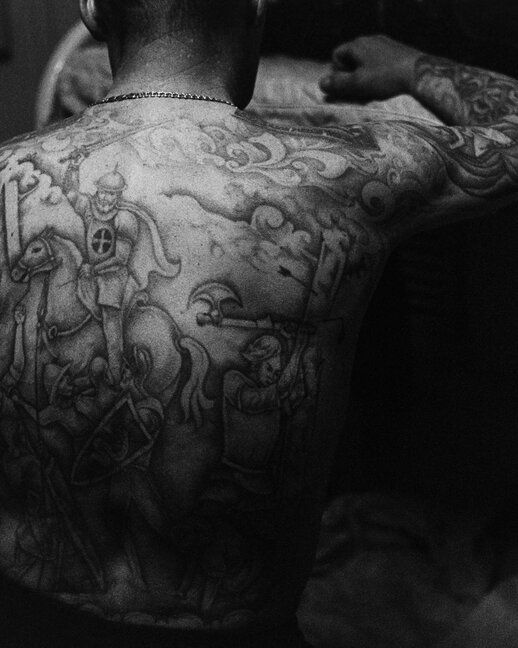

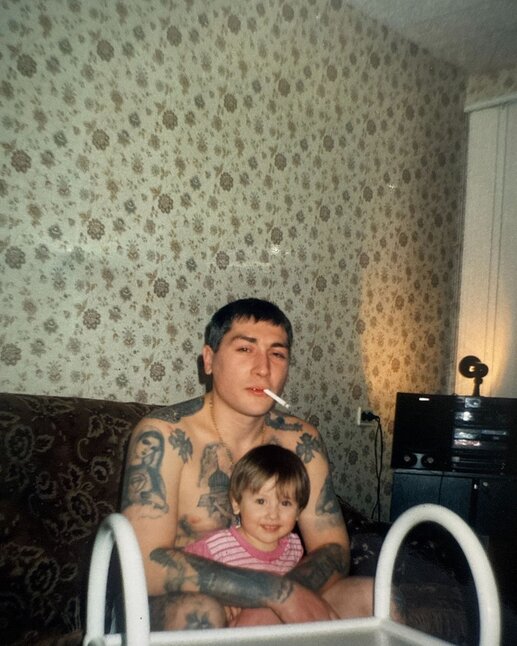

The codes were specific. A cathedral’s number of domes matched the number of convictions. A tattoo of Lenin or Stalin on the chest wasn’t a sign of loyalty; it was a challenge. Executioners were superstitious and hesitant to shoot through a sacred image. So prisoners turned icons into shields.

Technique mattered. Ink was made from burned rubber and urine. Machines were cobbled together from wire and razors. Tattooers were often Artists or craftsmen who were jailed for political dissent. Their skills earned them a unique currency in prison: respect, resources, and protection, but their time belonged to the collective. Some tattoos were voluntary. Others were forced. But every one of them meant something.

The 1980s: A New Era of Symbolism

By the 1980s, the meaning behind a tattoo had shifted again. Skyscrapers, drugs, cash, and violence became prominent. The imagery grew sharper and bolder, influenced by the crime economy and a declining state. Meanwhile, the government cracked down harder. Tattooing didn’t go away; it simply became more intelligent, more intricate, and layered, but over time, it slowly faded.

DIY tattoo machine sputnik razor from the 1980s.

DIY rotary machine power supply from the 1990s.

Post-Soviet Silence and Stigma

In post-Soviet Russia, prison tattoos were both taboo and surrounded by myth. Most people avoided discussing them, museums refused to display them, and many older prisoners had them removed or covered up. However, Herman Deviashin was determined to understand them, not only the symbols but also the stories behind them.

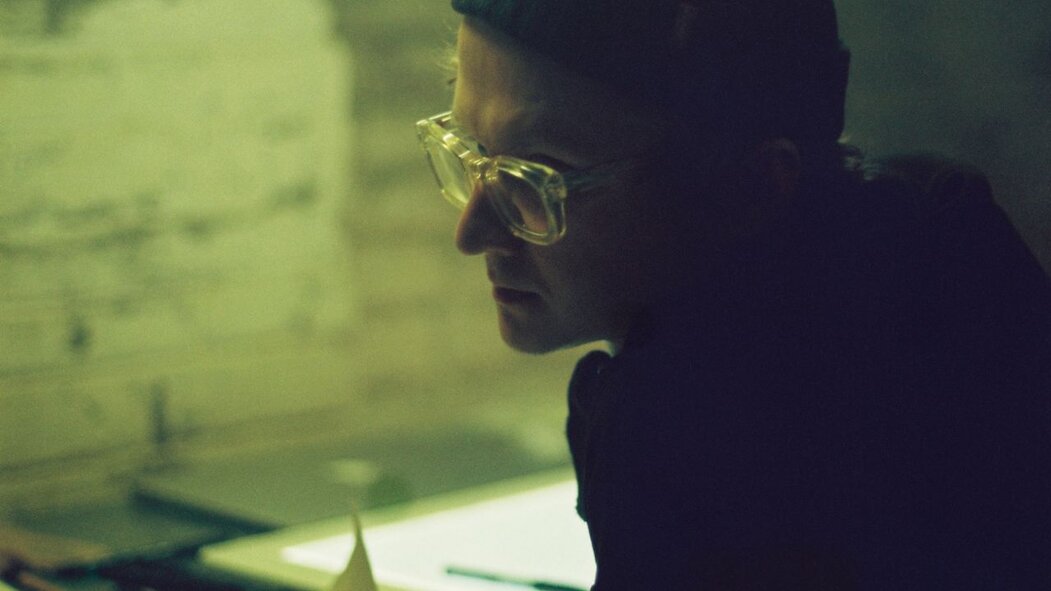

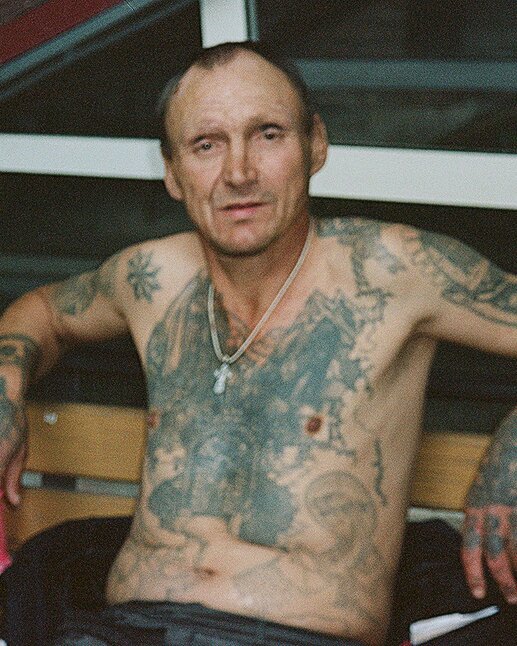

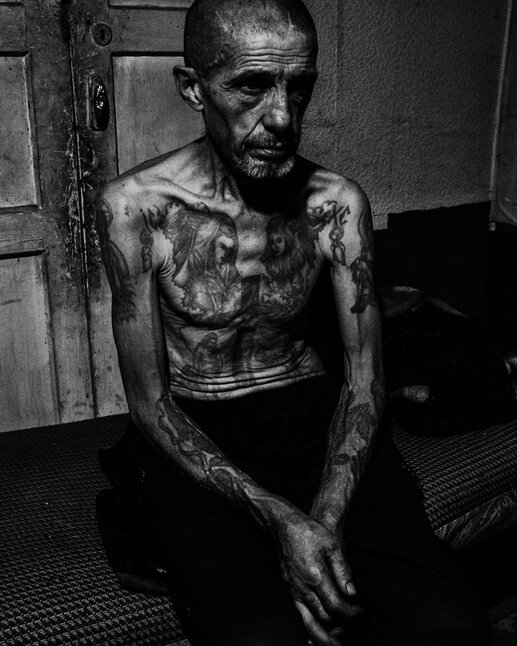

Herman Deviashin: The Body as Archive

As an Artist and researcher, Herman has dedicated years to collecting evidence of tattoo traditions that have never been officially documented. He treats skin like an archive. Each tattoo tells stories of timelines, journeys, traumas, jokes, and rules. The same care found in traditional icon painting is evident in a prison backpiece. The same logic used in ceremonial marks by Indigenous women is reflected in the coded domes on a Soviet prisoner. Power structures may change, but the body remains constant.

Global Fascination, Local Silence

Today, there’s a global interest in Russian prison tattoos. In Asia and the West, they’re viewed as edgy, mysterious, and even trendy. But in Russia, they still carry a stigma. Herman is often asked if wearing one is dangerous. It’s not. The real risk, he says, is erasure.

This History Matters

Most official archives won’t handle this material. Tattooing is considered too informal, too criminal, too human. That’s exactly why it matters. Herman has found missing people through old tattoos. He’s helped create accurate tattoo histories for Russian characters in films. He’s tested historical techniques on silicone to observe how the pigment reacts. He’s building an archive, piece by piece, even as institutions stay silent because history didn’t disappear; you just need to know how to read it.

12-year-old Alyosha Lebedev, a survivor of Auschwitz, shows his prisoner number tattoo, February 1946.

Tattoo of an anchor and lighthouse on skin.

Paskevich passenger getting his arm tattooed, Nagasaki, Japan, 1889.